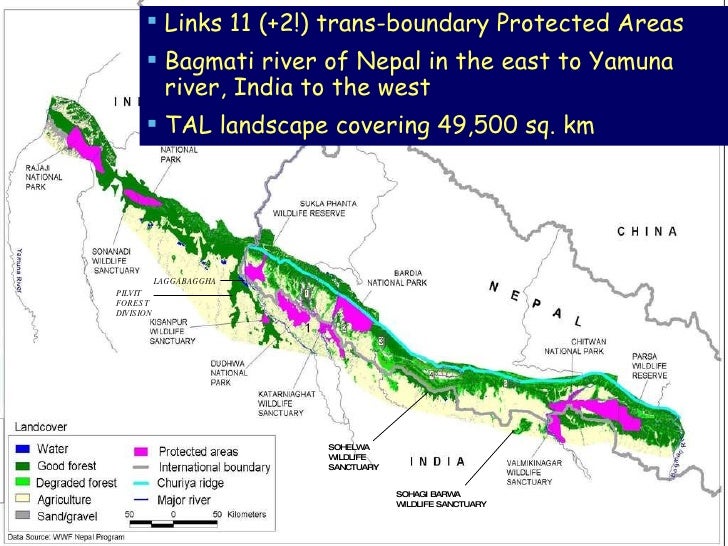

Along the Indo-Nepalese border, the two countries have achieved an impressive feat. In the most densely populated areas of the both India and Nepal, a network of 12 protected areas were established along the 1000 km long Terai Arc that creates one of the most important wildlife corridors of the Indian Subcontinent. Many of the national parks, tiger reserves and wildlife sanctuaries in this network are wildlife hotspots and tourist magnets for wildlife watching, like Pilibhit Tiger Reserve or Chitwan National Park.

A fighter for Suhelwa

However, during our second stop in India, we learned that especially smaller and lesser-known sanctuaries face a whole horde of problems. After leaving Pilibhit Tiger Reserve behind, we get a tip that there is a person and place we should visit: Niharika Singh and her Tapovan farm located just outside the Suhelwa Wildlife Sanctuary. Mrs. Singh has started coming to Suhelwa as a little child and fell in love with the place immediately. Later on, she moved here and started noticing all the problems that Suhelwa is facing. Since the early 2000s, she has been fighting to protect Suhelwa and put an end to the variety of illegal activities happening inside.

“I have been visiting Suhelwa since I was 5 years old , accompanying my family on Shikar trips. Back then the area was not protected and hunting was still allowed. Deer were plentiful as were other ungulates, including sambhar. Suhelwa supported a good tiger population. In the evenings, the forest lit up with the eyes of deer and other animals.”

Niharika Singh

While Suhelwa is not as popular and some national parks in the Terai Arc, it is by no means irrelevant. The 452 km² – plus 220 km² buffer zone – large wildlife sanctuary is an Important Bird Area identified by BirdLife International due to 11 (artificial) water bodies that were created in the mainly sal (Shorea robusta) dominated forest and grassland landscape. It is also an important stepping stone of the corridor between Bardiya and Chitwan National Park. But all of this is apparently not enough for authorities to take its protection serious.

“Suhelwa is more than a narrow strip of long forest. The international Indo-Nepal border is a manmade boundary which may gives rise to this notion, but in a real sense, Suhelwa is an extension of hills that forms critical wildlife habitat on the Nepalese side.“

Bivash Pandav of Wildlife Institute of India

Understaffed forest department

After our arrival at Tapovan Farm, we get the chance to accompany Gaurav Patel, a forest guard on his duty and witness the problems first-hand. Primary of them is a topic that the forest guard raises immediately: a lack of staff. The sanctuary only has 7 rangers or guards responsible for patrolling the whole 452 km². They commonly hire locals to support them, but do not get any funds for that meaning they have to raise this money themselves or find other means to pay, fueling corruption.

Mrs. Singh tells us that corruption is the biggest problem in Suhelwa. There are many illegal activities going on in Suhelwa and while some might go unnoticed, the employees of the forest department, that is responsible for the management of the sanctuary, are actually directly involved in many of them.

Firewood collection

Suhelwa is a thin, long strip of forest with settlements on both sides. The communities here traditionally live off the forest and still depend on it in many ways, especially to collect firewood for cooking and heating. During our trip with Gaurav, we pass dozens of people, including children on bicycles with huge loads of firewood strapped on the back. In the reserve itself, any extraction is forbidden, so the guard forces them to drop the firewood right were they are, confiscates their axes and sends them away. He also adds that normally, forest guards can even confiscate the bicycles. However, his strictness drops rather quickly and after the tenth or so intervention, people start passing us without any reaction by the forest guards. The highly surprised reaction of the collectors also makes it clear that they are not used to this kind of treatment. We suspect that what we witnessed in the beginning was rather a show put up just for us, which makes us quite uncomfortable.

Mrs. Singh tells us that the forest guards are actually often the ones overseeing all of these activities rather than restricting them. In return for crops, farm products or even unpaid ‘begar’ work, they allow locals to collect firewood, other non-timber forest products or even fell trees. Mrs. Singh has reported these horrible ongoings to higher authorities several times, even brought it all the way to the Indian supreme court. But except for short-term interventions and hollow phrases, nothing has changed. In fact, after fighting for Suhelwa for 20 years, Mrs. Singh has somewhat lost hope and reduced her involvement. She says that the situation is getting worse and worse and nobody cares about it.

Illegal logging

We get a glimpse of how bad the issue of illegal timber felling is at the sanctuary’s headquarters where confiscated logs are piling up everywhere. According to Mrs. Singh, this is only a fraction of all the timber being extracted. As we cross one of the eleven reservoirs inside Suhelwa, we witness another issue. It is dry season, therefore most of the reserve dried up and turned into a meadow, and hundreds of goats, sheep, cows and buffalos graze on this seasonal pasture. Around the reserve, there are no pastures, therefore the livestock has no other option but to feed on either plants growing on and between fields or in human settlements, where they are supplied with food or eat trash. This means pastures like the one inside the sanctuary are very valuable and create a lot of competition.

However, as a result, wild herbivores as well as the rich diversity of birds are scared by the presence of humans and livestock. As the livestock has to move through the sanctuary for long distances to reach the reservoir, they disturb wildlife and graze inside the forest on their way. The forest department tells us they have no resources to react. “We know this is illegal. But people have to bring their livestock somewhere, and there is no alternative,” explains Gaurav.

The situation gets worse

The negative impact of these illegal activities is enhanced by the bad management of Suhelwa. Water reservoirs have been drying up in the last years, because they are not properly maintained.

“In Suhelwa, things, species disappear in front of our eyes before we ever knew they were there.”

Niharika Singh

This is a serious threat for the unique bird diversity of Suhelwa as they rely on them. And because of the rampant corruption, the sanctuary’s management has no interest in developing the sanctuary for eco-tourism. Mrs. Singh has presented several plans on how to develop birdwatching tourism and made the first step herself by turning Tapovan Farm into a homestay. But for the forest department, more visitors mean more attention and thus more witnesses of their failure and wrong-doing.

Where can Suhelwa go from here?

On the upside, Suhelwa Wildlife Sanctuary is one of few remaining and protected forested areas in Uttar Pradesh and still an important corridor for tigers, elephants and other wildlife in the Terai Arc. On the downside, Mrs. Singh calls is the ‘doomed sanctuary’ because none of the rules in a wildlife sanctuary are actually enforced and the situation seems to be getting worse year by year. Especially on the Nepalese side, settlements are encroaching closer and closer to the sanctuary and Mrs. Singh observed a dangerous attitude amongst the young generation in the region who seek their own benefit within a system of illegal activities and corruption rather than the benefit for Suhelwa.

Over the last three decades, Mrs. Singh made plenty of suggestions how to improve the situation. Of course, illegal activities have to be stopped. For that the forest department must provide enough staff with sufficient salary to actually surveil the sanctuary. The next step is their training, so they can conduct targeted activities to protect wildlife. This means maintaining the reservoirs, identifying nesting sites, managing grasslands, as well as educating locals and helping them with human-wildlife conflict, e.g. boars destroying fields.

An important step would also be to zone the sanctuary, meaning that certain area are open for grazing or non-timber forest products, because currently local communities rely on them and their livelihoods must be protected, too. A great possibility for that is the development of eco-tourism utilizing the unique bird diversity. Mrs. Singh has suggested the establishment of homestays, training youth as bird guides and creating events like bird festivals to grow this sector.

It’s all about the attitude

Mrs. Singh and other activists have shown ways to improve Suhelwa’s situation over and over again. The issue is clearly not the lack of possibilities, it’s the attitude of officials and locals. Both see the sanctuary as a source for income and don’t want anyone to interfere in their system. Last year, an activist was even killed for speaking up. This naturally creates an atmosphere of fear amongst anyone who actually wants to protect Suhelwa and this is exactly what has pushed Mrs. Singh into a feelable state of desperation.

But Suhelwa is not doomed yet. WWF, the Wildlife Institute of India and other institutions as well as Sonika Kushwaha, the wildlife biologist that connected with us Mrs. Singh, have done studies in Suhelwa and raised awareness for its faith. And Mrs. Singh has a clear message to all of us about how we can help:

Please write about Suhelwa and share it with as many people as possible. Maybe this attention will help Suhelwa´s remaining inhabitants.