Bangladesh is the land of water. Its rivers rush down from the Himalayas, flood ponds, create wetlands, shape islands, and at the southernmost edge of the Bengal Delta, they form the Sundarbans, the world’s largest continuous mangrove forest. This tidal jungle stretches across an area of 10,000 km² shared by Bangladesh and India, and consists of a mosaic of islands separated by countless winding creeks and rivers.

Due to climate change and continuous logging however, the Sundarbans region is undergoing one of the fastest rates of coastal erosion in the world. Its communities are increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events such as cyclones and flooding, while salinisation caused by rising sea levels and reduced river flow harm local agricultural practices.

This is the place where we meet BEDS, the Bangladesh Environment and Development Society, an NGO building the capacities of the Sundarbans communities and restoring the ecological balance of the region. As we spend time with the team, we quickly understand that their work represents the dictionary definition of community involvement – a term that is so often used in nature conservation but is practiced with varying success.

“Many people near the Sundarbans live in poverty, therefore conservation must provide clear benefits and livelihood,” explains Maksudur Rahman, the Chief Executive of BEDS. And indeed, over the course of the upcoming days, we learn how BEDS paved the path of sustainability for local communities, while also focusing on improving their socio-economic condition.

The trajectory of the Sundarbans

For most of history, the Sundarbans mangrove forest was impenetrable and therefore remained virtually devoid of human interference. It remained like this up until about 220 years ago, when the colonial British administration decided to convert this land and introduce agriculture, first by cutting down the forest. As there were no communities living close by, labor was brought in from other regions, first for the logging of the forest, after which these communities settled down as farmers. In 1875, when more than half of the Sundarbans had already been cleared, the remnants of the jungle gained protection as a reserved forest.

After independence from British rule in 1947 and the division of India and Pakistan, religious conflicts brought many refugees to this area. Today, three-fifths of the Sundarbans lie in Bangladesh and two-fifths in India. It is an ever-changing habitat, new islands emerge as others disappear. The Sundarbans have the highest species diversity of any mangrove forest in the world. Dolphins, crocodiles, sharks and porpoises inhabit the Sundarbans region. It also provides a refuge to about 300 species of fish and 450 species of birds, while 34 out of 65 true mangrove species also occur here.

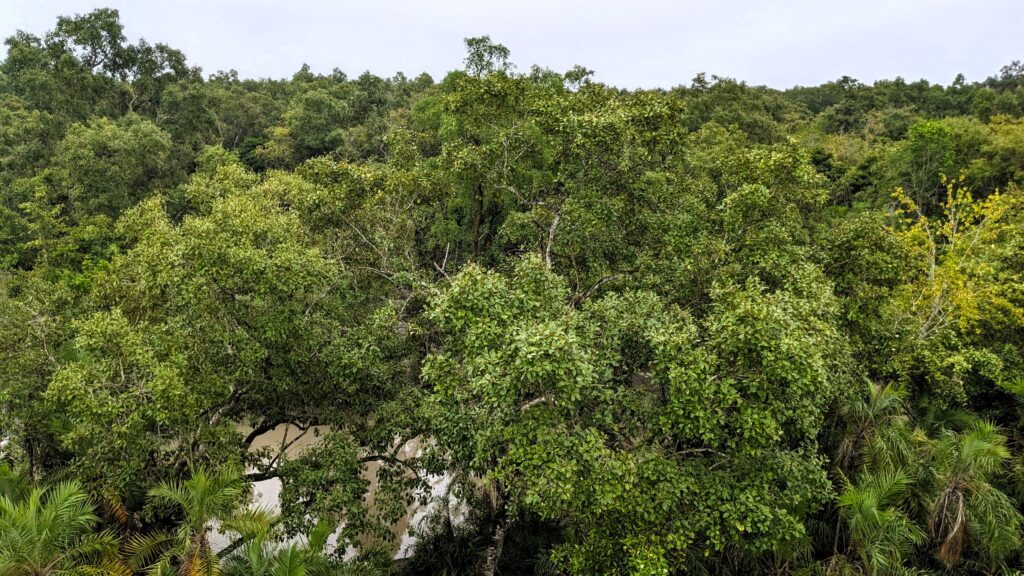

Impressions of the Sundarbans

In parallel, human population density around the forest is still rising, and many people here live below the poverty line. For their survival they rely on what the forest provides, and work as fishermen, woodcutters or honey collectors. Traditionally, most people utilizing forest resources follow unwritten laws of the community, and take only what they need. But as the population rises steadily, so does the number of livelihoods the forest must sustain. New people enter the forest and waterways, and work without the knowledge or respect passed down through generations. In the long run, this over-exploitation of the Sundarbans is the very act that threatens their own livelihood. The Forest Department sells permits for wood-cutting mainly to local merchants, who then employ wood-cutters for the season. The demand for forest products is high, and although the regulations are restrictive, illegal logging is common on both sides of the border.

The use of trained Indian smooth-coated otters for fishing is a vanishing traditional technique unique to the Sundarbans. The otters are bred, trained and traded by the last remaining otter fishermen.

Without the protection of mangroves or human-made embankments, the shorelines get eroded, and natural calamities like storms, cyclones and whirlpools impact the Sundarbans people more severely. When they go fishing into the jungle, they face encounters with tigers, crocodiles, poisonous snakes and even river pirates. They are dependent on the resources of the Sundarbans, but how can they access them sustainably and safely?

The dense jungle and saline muddy soil of the Sundarbans, a seemingly inhospitable habitat is in fact full of life. This environment is heaven for small crabs, mudskippers and snails. They attract wide varieties of predators, like snakes and birds, which feast on the plentiful prey.

A new, holistic framework for communities

It becomes clear to us that the Sundarbans plays an important role in the economy and livelihood of the southwestern region of Bangladesh, especially as it is the largest single source of forest products in the country. The organisation BEDS was founded in response to these threats to maintain ecological balance and create harmony between humans and nature. Their work covers a multitude of topics from climate change adaptation and mitigation, sustainable livelihoods and wildlife conservation to children’s rights as well as gender equality.

When we arrive in the Sundarbans, BEDS invites us to their Banojibi agro farm, a unique initiative established by BEDS but largely managed by the local community. Banojibi is a Bengali word, at it means the people who depend on the forest’s resources. “Banojibi is a cooperative society, which was created to improve the livelihoods of locals through bringing the production, processing and marketing of Sundarbans resources under one umbrella,” tells us Sanjida Yeasmin, project manager of BEDS as we walk through the farm. The shelves of the packaging room are filled with mangrove pickles, mangrove honey, molasses and dry fish manufactured by the cooperative, which currently has over 260 members. Livestock rearing and ecotourism are further income sources for the cooperative. Visitors can stay in comfortable cottages, taste dishes made from locally grown vegetables and Banojibi products, and can even visit the Sundarbans on a boat tour.

The Banojibi agro farm is set up by BEDS and managed by the local cooperative society.

“Banojibi belongs to you, me and all of us,” states a poster on the wall. Indeed, as we walk around the farm, we see locals actively working in gardening, feeding the sheep and fishing. The farm is all powered by solar energy, while a big water filtering system for safe drinking water at Banojibi is open to the community.

Such a holistic approach is very important for us, protecting the mangrove ecosystem and in parallel improving the living standards of the Sundarbans coastal community.

Maksudur Rahman, the Chief Executive of BEDS

Maksudun Rahman (left photo) and Sanjida Yeasmin (central and right photo) explain the holistic approach of BEDS. Aside ecological restoration and sustainable livelihoods, they invest in clean water, disaster risk management, children’s and women’s rights. They aim to uplift the community along the lines of sustainability in every possible way.

Community-based mangrove restoration

Although we are in the midst of the rainy season, we put on our rain protection and take a walk with Sanjida. We visit a few mangrove plantations that are planted as natural flood barriers. These mangroves are planted along concrete embankments. “These embankments were built here to “beautify” the coastline,” we learn from Sanjida. This sounds ridiculous to us at first, but later, visiting more remote villages, we experience first-hand that without paved, concrete roads, the village roads turn into slippery mudslides during the rainy season.

Last year only, the BEDS team and the local communities planted 365.000 mangroves and restored 32 hectares of land.

Looking at the dates of planting in different sites, it is truly astonishing to us how fast mangroves grow due to their adaptation to an ever-changing environment. For stability and respiration in the muddy forest floor, they have developed aerial roots. These roots pierce the mud and keep it compact, and excrete excess salt through special glands in bark, roots or leaves. The seeds mature on the tree and then drop to the ground, where they either stick in the mud and rapidly develop roots, or are carried away by currents, which is why the coastlines everywhere here are covered in mangrove seeds.

Would you guess that these are all mangrove seeds?

Sustainable aquaculture in mangrove ecosystems

Continuing our walk, we arrive at the new sustainable aquaculture center of BEDS. “One of the causes behind the ongoing mangrove forest destruction is the continuous expansion of shrimp aquaculture, and at the same time, shrimp larvae are caught in alarming proportions in the wild, to satisfy the increasing demand,” explains Sanjida. To make shrimp farming even more complex, there is a long supply chain in Bangladesh, with several intermediaries between the farmer and the processing company. This puts farmers in a vulnerable position economically.

BEDS wants to teach farmers the benefits of mangrove protection within shrimp farms and improve the whole value chain to make it more reliable. A new cooling station under construction will be handed over to the community once finished, and will provide locals with appropriate cooling rooms to store their products longer.

The big picture

Visiting the Sundarbans has been a long-standing dream of ours. We knew that their network of islands, river streams and impenetrable forests form one of the most biologically complex ecosystems on Earth.Finally, we got to marvel at this complexity with our own eyes. Even though, due to the rainy season, we were not able to get deep into the mangrove labyrinth, we could instead spend our time with coastal communities and conservationists living with and off this unique ecosystem.

Local communities are just as deeply intertwined in the Sundarbans region as the mangrove roots in its muddy soil. BEDS builds the capacity of these most vulnerable communities and introduces ways to sustainably use the natural resources of the Sundarbans, not by making decisions in a far-away office, but by working in the community. Teaching the community how to work as members of their cooperative, how to share responsibility and how to harvest the fruit of their joint work, while respecting the principles sustainability is incredibly valuable looking at the future of the Sundarbans. The mission of BEDS reminds us of the old wisdom “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man how to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” Thanks to the enduring effort of BEDS to implement sustainable solutions hand-in-hand with locals, there might just be enough fish to feed everyone in the Sundarbans.