Throughout our journey we have regularly heard about conflicts with hunters from conservationists. In several Central European countries, wolves and bears are extinct due to overhunting, in the Caucasus even deer have disappeared in many places and birds are being killed for fun all over the place. And also in Pakistan, illegal hunting or poaching is a huge issue for many game species. But in the far north of Pakistan, in the region Gilgit-Baltistan, strictly regulated trophy hunting has turned hunting from a threat into possibly the most efficient nature conservation tool.

Hunting as a problem…

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to some rare ungulates like Himalayan Ibex, Blue sheep, Ladakh Urial and Astore Markhor. Due to their rarity, the inaccessible terrain they live in and their impressive horns, they are popular amongst trophy hunters. This has also led to a significant decrease of their numbers in the 20th century. Unsustainable and often illegal hunting in combination with rising livestock numbers in their home range, that compete for scarce pastures, have brought numbers significantly down. To this, the Pakistani government reacted with a strict law introducing harsh penalties and prison sentences for poachers in 1979. However, the new regulation had little impact in remote Gilgit-Baltistan, where the Pakistani government has little influence and the landscape is so rugged and sparsely-inhabited that poachers don’t have to fear being caught.

…trophy hunting as a solution?

So, in the 1990s, the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme in cooperation with IUCN and WWF proposed another idea to stop poaching and rehabilitate ungulate populations: trophy hunting. The goal was to give local communities a monetary incentive to preserve their wildlife, involve them directly in conservation and use the generated income to improve local infrastructure. The Pakistani government approved the system and started auctioning licenses to (mostly foreign) hunters. Quotas are defined for the territory of each community in Gilgit-Baltistan depending on the population of each species in the area, which is monitored three times every year. Each license is then auctioned off to the highest bidder.

What do locals think?

To get a first-hand impression of this system, we meet Manzoor Ahmed Qureshi, Programme Manager for Natural Resource Management at the Gilgit-Baltistan Rural Support Programme. In this position, he acts as a link between local communities and the government in all kinds of nature conservation topics. He takes us to the villages Bunji, Nagar and Maiun, where we talk to locals to hear their thoughts on sustainable development and trophy hunting.

Our first stop is Bunji, a village in the lower part of Gilgit-Baltistan. When we arrive, we are surprised that the men of the village have gathered to meet us (photo below), and share their nature conservation efforts. We did not expect that so many people are interested and involved in managing their natural resources. All of them seem convinced by the trophy hunting system and proudly tell us that the population of markhors has tripled in their territory since the system was introduced 30 years ago. Last year, a hunter paid 130,000$ for a single markhor in Bunji. 20% of that money goes to the government, the other 80% goes straight to the community that communally decides on how to spend it. This revenue enabled them to build new infrastructure in the village, to construct a community center and enlarge their fields and orchards, which remain their most important source of livelihoods.

Communizing nature conservation

The main advantage of these ‘community managed hunting areas’ (CCHAs) is that they are protected by and not from the local community. Too many times throughout our journey, we have seen protected areas that are heavily-guarded or even fenced to prevent locals from entering and harming nature. This creates public opposition towards the protected area and generates massive costs. In contrast, the trophy hunting income makes CCHAs economically profitable for locals and they take care of its protection themselves. Manzoor calls this system “social fencing”, where the whole community partakes in securing the CCHA. From the trophy hunting income, they also pay a few ‘wildlife guards’ within their community, who regularly patrol the area and make sure no illegal activities take place. On top of that, these wildlife guards can also be involved in wildlife monitoring, they can regularly check camera traps and inform the local organizations of any interesting findings.

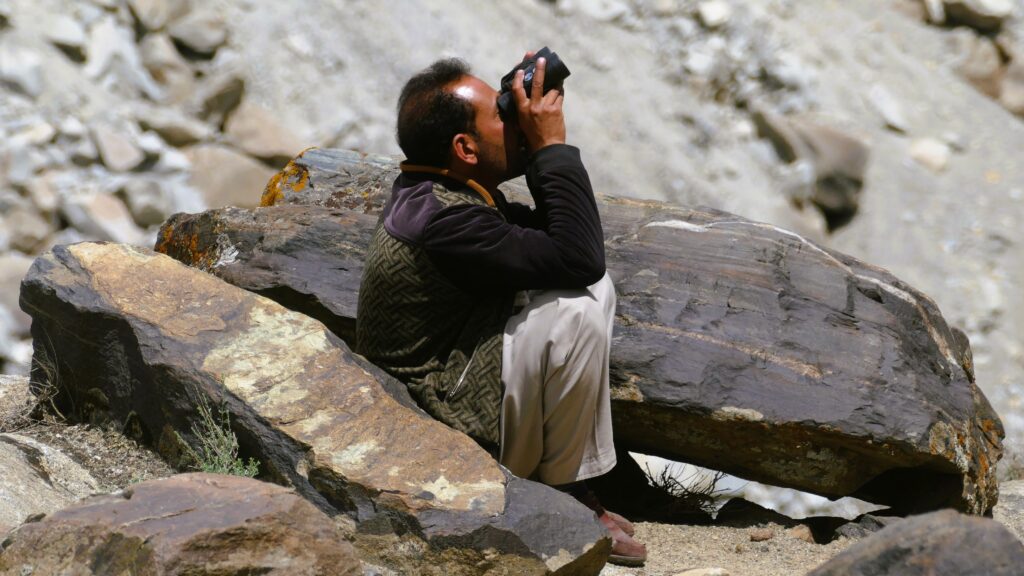

We experience how well they know the mountains first hand, when we visit the village Skyo with Raza Mohammad, Program Officer at ‘Baltistan Wildlife Conservation and Development Organization’ (BWCDO). We are here to speak to the community while also hoping to spot ibex and markhor with our own eyes. Without local help, this is almost impossible as they are well-hidden in areas that are impossible to reach for humans. So, we set out with two of the wildlife guards, both called Mushtaq, with hope and anticipation. While we see nothing but endless rock around us, Mushtaq and Mushtaq know exactly where to look. And indeed, at our second location, they spot a herd of ibex on a faraway slope, who are resting under the midday sun.

So, is hunting bad or good?

With our own predisposition that hunting = bad, we were very curious to find out what conservationists and local communities think about this system. After talking about this topic with people across Gilgit-Baltistan and also other parts of Pakistan, we are surprised how universally positively it is assessed. In a country like Pakistan, where many people still live off their land from hand to mouth, economic profit is the most effective way to convince people of managing their natural resources sustainably. With a growing population, depletion of resources and serious economic issues like massive inflation, nature conservation is very much a secondary topic in Pakistan. People use up land and water to grow crops and rear livestock, but at the same time, both resources dwindle, accelerated by climate change. Wild ungulates in this scenario are competition for livestock and the cheapest source of meat.

Nature conservation must pay off

The regulated trophy hunting, however, turns wild ungulates into an asset that is much more valuable than some fields or pastures. Before the system was introduced, wealthy hunters already came to hunt these animals, but did it on their own or by paying a few villagers mere amounts to guide them to the animals. The trophy hunting system does not only create much more revenue, this revenue also benefits the whole community instead of just a few individuals. It incentivizes sustainable management, close monitoring and tight safeguarding of wildlife.

In Pakistan, this system is so popular that is an integral part of new nature conservation projects. In the Salt range, a small mountain (or hill) range south of the Himalayas, the Punjab Wildlife Department is currently planning the reintroduction of several ungulate species that became locally extinct and threatened due to habitat loss and overhunting. Introducing trophy hunting, as soon as the populations are stable enough, is an integral part of the project and one of the main selling points to local communities as one of the few ways that nature conservation can bring direct and significant income to locals. The international nature conservation community also noticed the successes and Manzoor was invited to present at the ‘7th World conference on mountain ungulates’ in the USA in 2020. Just like us, participants were impressed how successfully the system works and how many benefits it brings to local communities.

Don’t hate the player, hate the game

On a personal note, we still cannot relate to the joy of hunting and the willingness to pay 130,000$ to kill an animal and hang it on your wall. But from a nature conservation perspective, we have to admit that up until now, we have possibly never seen a system that brings so many direct benefits to local communities and hence make species protection their priority. The growing population numbers of ungulates in the concerned areas speak for themselves and naturally have a domino-effect on predator populations. In Bunji, we also saw that in can pave the way to a more wholistic system of nature conservation. The community plans to establish a first-of-its-kind ‘Ecosystem Conservancy’ on its land that regulates issues from grazing to farming, eco-tourism and so on.

Killing vulnerable species is always dangerous

Important is that system is closely monitored by IUCN and maintains its integrity. Shafqat Hussain, founder of the aforementioned BWCDO, has criticized that corruption has crept into the system and more licenses are given out than the quotas allow. Ali Usman, Deputy Director Wildlife at the Punjab Wildlife Department, adds that such kind of conservation mindset among communities might have harmful effects as conservation efforts are focused on trophy species, not the whole ecosystem. And if natural predator numbers increase, they might see them as a threat to their valuable assets.

These examples show that this system is also not perfect and must be critically evaluated on a continuous basis. Nevertheless, it presents a way how local communities can actually have the power over their land and make major decisions about their natural resources communally.

Pingback: A holistic conservation success story – Livestock insurance scheme to protect snow leopards - biking4biodiversity.org