The Angkor Centre for Conservation of Biodiversity, one of Cambodia’s first wildlife rescue and breeding centres is making outstanding achievements in the conservation breeding of globally threatened yet often overlooked species.

A centre for wildlife rescue, rehabilitation and release

Close to the infamous UNESCO World Heritage Angkor Wat temple complex, there is a very significant place for wildlife conservation in Cambodia and South-East Asia as a whole. It is morning when we arrive at the closed gates of the Angkor Centre for Conservation of Biodiversity (ACCB), where country director Christel Griffioen welcomes us in. As we follow her, we slowly hear all the animals at ACCB waking up. Among a gibbon concert, chirping of the Alexandrine parakeets and the playful high-pitched sounds of smooth-coated otters fill the air.

“About 96% of all animals in the centre belong to a threatened species,” explains Christel, as she guides us along the first enclosures. Established in 2003, the centre inside Phnom Kulen National Park serves as a place to rescue, rehabilitate and breed some of Cambodia’s most at-risk wildlife, with a key focus on turtles and water birds. “We currently have about 1000 animals here, about 80% of which are endangered and critically endangered turtles,” we learn from Christel. The conservation centre was established by the Allwetterzoo Münster in Germany and by the Zoological Society for the Conservation of Species and Populations. The organisation has cooperated with several other NGOs in wildlife conservation, and nursed both illegally trafficked animals, and animals found injured in their natural habitat back to health. Just a few of these species include the Giant ibis, White-shouldered Ibis, Greater and Lesser Adjutants, and Sunda pangolins. Wild animals are also brought to the ACCB through the pet trade, with a common theme of individuals buying a wild animal with the intention to save it. “Many people simply don’t know that keeping wild animals is illegal in Cambodia, and when they find out, they are often happy to give the wildlife under their care to ACCB,” Christel explains.

This greater adjutant stork, crested serpent eagle and common leopard cat are only a few of the species living in ACCB.

ACCB then aims to rehabilitate them in a hands-off approach. Keepers limit interactions with the animals that can be released, and where possible they are released directly around the centre and in secured protected areas within their natural habitat. These releases are undertaken in collaboration with relevant government authorities and conservation partners. To those animals that, for a multitiude of reasons may not be suitable to be released, like a wide range of birds and mammals, including Asian woollyneck storks, Oriental pied hornbills, pileated gibbons, smooth-coated otters and leopard cats, the ACCB has become their home.

Pileated gibbons are master brachiators. They swing from tree to tree using their long and strong forearms, able to jump up to 15 metres in distance. On the ground, gibbons are able to walk bipedally just like us humans, but hold their hands above their head, which helps them with balance and staying upright.

However, the main focus of the centre has shifted over time, and conservation breeding has come into focus. “Our main attention has shifted from the rescue of individual animals in need to species conservation, especially concentrating on endangered and critically endangered water birds and endangered turtles; species that are often thought to be less charismatic, but whose long-term survival massively depends on the actions we take”, Christel explains. “There is a definite need for ex situ conservation, which is why we are focusing our breeding programme on establishing insurance populations for some of Cambodia’s rarest species. The long-term goal is to reintroduce captive-bred individuals into secure, protected, areas within their natural range, a goal that works collaboratively with in-situ ecosystem restoration.”

Ex situ breeding to save endangered species

Around the globe, habitats and ecosystems are becoming increasingly altered and their inhabitants continuously impacted by human activities. A growing number of species require some form of management to ensure their survival, this is where “ex situ conservation” comes into play. According to IUCN, “…ex situ is defined as conditions under which individuals are removed from many of their natural ecological processes and are managed on some level by humans.”

Christel is very interested in ex situ conservation, especially as habitats continue to decline, transform and become increasingly unsuitable. For many native species in Cambodia this means that ex situ management may play a critical role in preventing their extinction. Take the Bengal florican for instance, one of the rarest bird species in the world. This species has a global population of less than 1000 mature individuals and is listed ‘Critically Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List. Cambodia is one of the last places where it occurs in nature, but its habitats are decreasing by the minute as grasslands are being converted into rice fields, habitats are becoming progressively more fragmented, and human disturbance increases.

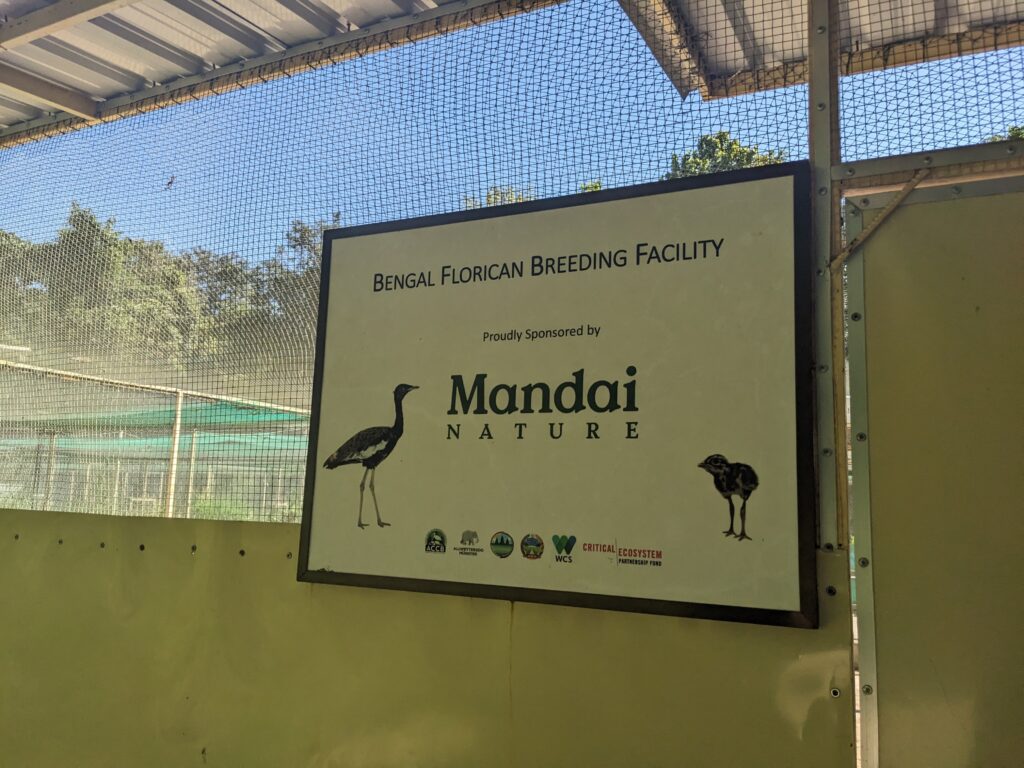

Therefore, as part of an ex situ conservation program, the ACCB and their project partners established the first-ever Bengal florican breeding facility in the world. Christel explains that eggs are sustainably collected from their natural habitats in the wild, ensuring the smallest impact on the wild population. “We take the first eggs of the season to enable the individual to lay a second clutch. We also take those eggs at the end of the season that are at risk of drowning from the seasonal flooding” tells Christel, whilst proudly sharing that after artificial incubation, and hand-rearing by experienced caretakers, the 2023 season saw a 100% hatching and rearing success of fertile eggs at ACCB. The organisation also became the first facility where a Bengal florican egg was laid in captivity.

The assurance population in the centre is completely shut away from visitors to ensure that birds are not disturbed, which potentially could impact breeding results, and to avoid birds to become overly habituated to humans, ensuring they grow as wild as possible.

At the same time, Christel explains their focus on involving local communities in the conservation of this critically endangered bird and other species. “In collaboration with captive breeding, conservationist and government partners have to put a lot of effort on protecting the existing wild populations and their habitats. That’s why local communities in Cambodia have an important role, and it is only together that we will be able to save species from extinction,” she emphasises.

Milestones in conserving those who receive less attention

It is not only the Bengal florican that faces lethal threats from land conversion. Illegal logging, poaching and development is transforming Cambodia’s natural landscapes. Natural habitats are disappearing, which produces heart-breaking stories for many other species. For example, there are less than 300 Giant ibis left in the world, and three of them are here at ACCB. The Eastern Sarus crane is a subspecies with three separate populations in Cambodia-Vietnam, Myanmar, and a reintroduced population in Thailand. Nowadays the Cambodia – Vietnam population consists of around 200 individuals only, of which two are long-term residents of ACCB. ACCB is also the only facility worldwide to breed White-shouldered ibis, with the first successful hatching at the beginning of 2023.

The endangered Greater adjutant, and the vulnerable Lesser adjutant and Sarus crane share their space but keep their distance.

But the majority of inhabitants at the centre are turtles. The Indochinese southern river terrapin is a critically endangered species, one of the world’s most endangered tortoises with only 700 remaining from its formerly widespread population, Its numbers have drastically declined due to poaching for its meat and eggs. The ACCB is one of the only two places where this terrapin species has been successfully bred. Additionally, after unsuccessful attempts since 2015, in 2023 the critically endangered yellow-headed temple turtle laid a clutch at the centre for the first time. Christel tells us that the ACCB has established assurance populations for turtle species and has started introduction programs for captive-bred, head-started, offspring. Releases happen once the young turtles reach a size and weight where they are less prone to predation and the individual is able to survive independently. The captive breeding results of recent years are a promising sign for the future of these species.

The Indochinese southern river terrapin was thought to have disappeared from Cambodia until it was rediscovered in 2001. Its eggs were a delicacy of the royal cuisine of the country. In 2005, it was designated the national reptile of Cambodia in an effort to bring awareness and conservation for this species.

The list of successes goes on, which not only proves the expertise of the ACCB team in conservation breeding, but also makes one feel that there is still hope for those species at the very brink of extinction. The tides can still turn and with focused effort, once the immediate threats to the species have been addressed, ex situ populations can be released and used for population restoration.

The ripple effect of awareness raising

ACCB is open to the public. There are two tours a day, to a maximum of 20 people each, and it is also possible to schedule visit outside of those hours, based on availability. Only a minimum donation is requested from visitors, and locals are exempt from paying admission for the daily scheduled tours. “We are trying our best to educate locals about conservation issues in their country. It is not uncommon that people visiting our centre are not aware that keeping wildlife as pets is illegal in Cambodia,” Christel tells us. And with 3,000 visitors per year post-Covid (pre-Covid 6,000 visitors per year), the centre has a large potential for shifting people’s perceptions about wildlife trade. Members of the staff also gain a lot of awareness and knowledge about wildlife while working here, and become ambassadors of conservation themselves. Now, Christel tells us that whenever an animal is released, ACCB informs locals in advance and involves rangers as well, which means that any illegal attempt of hunting would likely be found out within the community.

One of the most interesting outreach activities Christel tells us about is the program collaborating with Buddhist monks. Since 2021, conservationists have been visiting pagodas, educating monks about the environment, building a trusting relationship with them, and continuing to support them in their efforts to further educate the public, and build environmental consciousness.

“What gives me the most joy in my work is seeing the behavioural change in people over time. A shift is definitely happening.

Christel Griffioen, Country director of ACCB

There are many things about Cambodia’s natural heritage that are yet to be discovered, and with habitats shrinking and getting fragmented by the day, species may be disappearing right in front of our eyes without us ever knowing what we missed, or being able to intervene in time to protect them. This is what makes the efforts of the ACCB so crucial. In the tsunami of over-exploitation, they provide a small but significant fortress of conservation, providing not only a refuge and rehabilitation for rescued animals, but also create a stronghold for species that are barely, but still found in the wild.