In our previous article, we got the chance to talk with Dr. Ha Thang Long and learn about the work of his NGO GreenViet, saving the red-shanked douc of Son Tra peninsula and gradually changing the mindset of locals about the values of nature. As an expert in Vietnamese biodiversity, we were looking forward to talking with him about our observations of the protected areas we visited in the country, and learning about his work in the Central Highlands. After our conversation, we got the chance to visit a community in this mountainous region in central Vietnam, which is covered by the largest continuous forest areas in the country, and understand how to build up an effective protected area management in an area that has lacked sufficient management, law enforcement and community awareness in the past, resulting in devastating impacts for wildlife in the past.

The issue of paper parks

The term “paper park,” was first used in a 1999 WWF-World Bank report, referring to “a legally established protected area where experts believe current protection activities are insufficient to halt degradation.” This means that the park exists on paper, but in reality fundamental infrastructure and capacities are missing to achieve conservation goals effectively.

In Vietnam’s case, many national parks were established in the 90s, with no law enforcement present before and even after their establishment. Dr. Long recalls the ‘Sourcebook of Existing and Proposed Protected Areas in Vietnam’ published in 2001 by Birdlife International, which noted that lots of national parks only exist on paper in the country. “In the 90s, as I was working in Cuc Phuong National Park, I still heard gunshots and snaring was abundant,” he adds. “Vietnam is a developing country that has come out of war, and additionally, China and its market for traditional medicine is close.”

“Tourists expect as much wildlife abundance as for example in Costa Rica, but in Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, you don’t see much wildlife easily,” he confirms our observations travelling in mainland South-East Asia. Wildlife populations are rather low, and large mammals are mostly gone because of bad law enforcement. Instead, in this region, wildlife is on the path to recovery just now, and it needs local and foreign organisations to work together with governments and locals to shift the perception of biodiversity values. “You know, my generation is the first to have access to scholarships abroad, and foreign funds have been coming in since the 2000s, therefore we are finally observing a positive change.”

Protecting the Central Highlands, the home of rare primates

In the 90s Cuc Phuong National Park was the first location where the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) started a long-term project on biodiversity and langur conservation, largely focusing on the improvement of law enforcement.

In 2006, he and his young research team started working on biodiversity surveys in Kon Ka Kinh National Park – 42,000 hectares of subtropical rainforest – in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, close to his hometown Da Nang. Forests in the region provide a safe home to 16 primates species including langurs, gibbons, lorises and macaques. This park is home to the largest population of grey-shanked douc langurs, a primate species that is endemic to this place but is critically endangered.

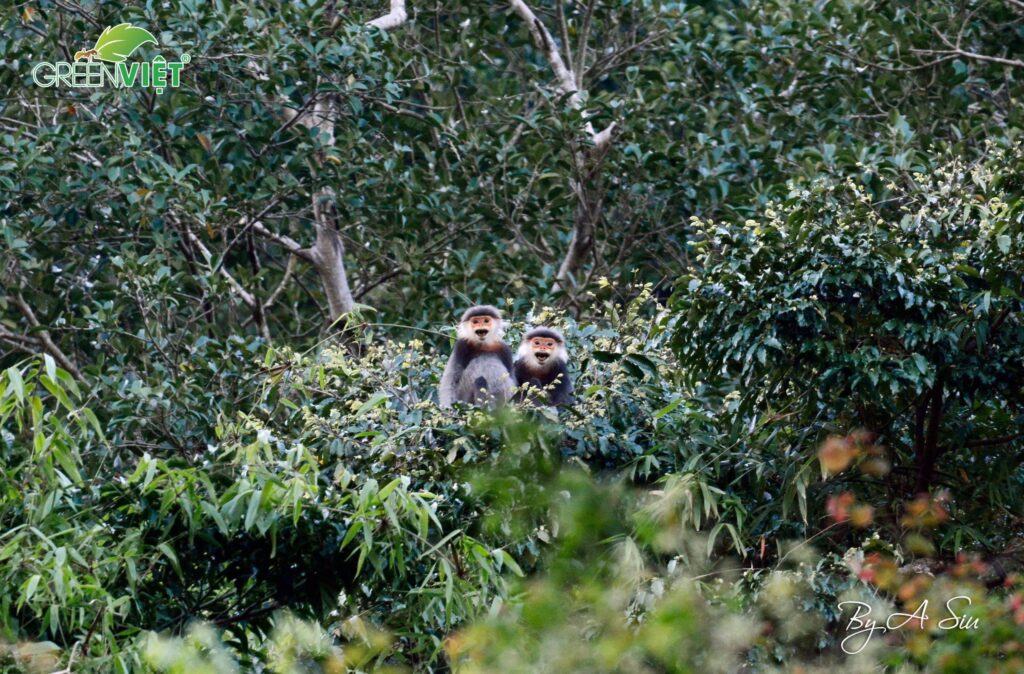

The critically endangered grey-shanked douc langur is one of the world’s most striking primates, and can only be found in the highlands of Vietnam. (Photos by GreenViet)

These efforts have since been expanded, and since 2010 Long is the project leader of FZS, responsible for Kon Ka Kinh National Park and since 2021, for the Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve, which together take up over 57.000 ha of habitat in the Central Highlands of Vietnam.

Long spent over 20 years, including his PhD, studying the behaviour and population dynamics of grey-shanked douc langurs, therefore he is very passionate about them. “This primate species is endemic to Central Vietnam and is critically endangered, with populations spread across various provinces but disconnected by growing agricultural fields and hydropower plants,” he explains. The park is also home to the northern yellow-cheeked crested gibbon, an endangered primate which also is found in the nearby Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve.

Therefore, in the last 13 years, Long and his colleagues at GreenViet and FZS have been working towards building up a working protected area management from the ground, a long-term effort that has already brought several successes.

The yellow-cheeked crested gibbon is born blond and later turns black. Males carry this colouring through their lifespan and have the distinguishing golden cheeks. Females are born blond to blend into their mother’s fur but they later turn black, after which they turn back to blond at sexual maturity, keeping only a black cap on the top of their heads.

Preventing illegal hunting

Like in other developing countries, the living standards of people living in rural areas are still low. Therefore, subsistence hunting is still an important way for many people to get food, and sometimes, they choose poaching as a profession to sell what they catch to earn an income. In Vietnam as well as in the rest of mainland South-East Asia, hunting is the biggest threat to the primates, both to the gibbons and the douc, since their natural predators are all gone from the landscape.

Therefore, one key aspect of the long-term project is to mitigate hunting in Kon Ka Kinh and Kon Chu Rang. This means that Long and his colleagues work side-by-side with the park rangers, training them to be able to conduct effective forest patrols and wildlife monitoring, while supporting them financially to do more frequent patrols. “Law enforcement has improved, but the salary of rangers is still low. Normally they are paid about 250 € per month, and from that amount they are expected to cover the fuel costs of patrols,” tells Long. Under such circumstances, they naturally want to save as much of their salary as possible to provide for their families. This is why the project of FZS supports the costs of patrolling, including fuel, food and communication. Rangers use SMART for patrolling, and since the first species surveys at the start of the project both the grey-shanked douc and yellow-cheeked gibbon numbers have increased.

“In such a tight community, being engaged in illegal wildlife trade has become a risk. There are government funds that go to the community, but if it becomes evident that someone from that community is actively poaching, it is the whole community that might lose funds, therefore there is an internal regulatory mechanism developing within the community” Long adds with optimism.

We head into the deep jungle of Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve.

Working with the local Bahnar community

The region is inhabited by the Bahnar ethnic minority, and the project has brought major improvements in community awareness, by working with locals and helping them understand that the douc and gibbons inhabiting these forests are becoming exceedingly rare. Through workshops and courses provided to children, they learn about the biodiversity of their home, its rare species and the dangers that hunting poses to their future.

“There are about 3000 Bahnar people living around the forest, which is why we are working with Bahnar leaders and getting them on board. It is very important for me to work with the owners of the forest. They know everything about the wildlife inhabiting these areas, and in fact I’ve learnt everything necessary for my PhD on the grey-shanked douc from them. They had the knowledge needed for a PhD way before me,” Long emphasises.

The project also tries to set up alternative income sources for locals based on ecotourism, such as working as tourist guides or creating a market for local products.

“If you want to stop people from poaching, you have to keep them busy, and provide them an alternative.”

Dr. Ha Thang Long, primatologist and founder of GreenViet

An impression of the Central Highlands

Talking so much about the Central Highlands, we are eager to finally experience the Central Highlands for ourselves. But before that, we stop at a small village near the coast, which has a group of about 70 grey-shanked douc living in the nearby forest. With Mr. Du, a local villager, we start an early morning hike into the mountains, only to find out that the forest we pictured is a last patch of natural habitat surrounded by vast plantations of acacia trees.

We don’t spot grey-shanked douc that morning, but looking through our binoculars within the sea of acacia, scanning this last piece of healthy forest, we are saddened by how fast their habitats are diminishing.

Continuing our journey through vast areas covered by coffee and citrus plantations, two days later we arrive at Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve, where Tây Nguyên is already waiting for us. He is a masters student who is responsible for studying the distribution of yellow-cheeked gibbons in Kon Chu Rang and Kon Ka Kinh. We have a rainy day ahead of us, nevertheless, Tây and the local rangers take us into the dense forest. As we make our way to the beautiful K50 waterfall in the heart of Kon Chu Rang, Tây tells us about his work.

“The gibbon monitoring is conducted in the dry season, between February and July. We have 12 points in the park, and we record the vocalisation of the gibbons in the early morning. At each point, we use a voice recorder to record their songs,” he explains. “Contrary to the douc, gibbons live in small family structures just like us, and each group has a different structure and frequency in its song. By recording their vocalisation, we are able to distinguish groups from each other, and by surveying the whole park, we are able to calculate how many of them are in the forest. Slowly but steadily, we are seeing an increase in their numbers.”

We spend the rest of the afternoon with the rangers, many of whom are from the Bahnar community. “About 80% of the community living around Kon Chu Rang is Bahnar, therefore they must be engaged in conservation,” Tây emphasises. Every protected area can hire a few local people, who don’t necessarily have the required qualification as a ranger. Moreover, on every patrol and wildlife survey, the responsible researcher and ranger is accompanied by at least one Bahnar local, which is an amazing idea that we are captivated by.

Photo impressions of our time in Kon Chu Rang.

Throughout the afternoon, the rangers show us around the Bahnar villages, we visit farms, eat delicious food and get to learn about their local traditions. When we ask one of the rangers what he loves most about his job, he replies “I just love being in the forest.” And this one simple sentence is enough to fill us with hope for these protected areas. When the locals, who know and understand the forest the most, get the chance to earn a living by protecting it, they can become its real guardians for generations to come.