After arriving in Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, we start our journey north. As Islamabad is located on the foothills of the Himalayas, there is only one way north into the mountains: the Karakorum Highway that runs along the Indus for over 500 km until Gilgit-Baltistan. It is a remote region that connects the three highest mountain ranges of the world, the Himalaya, Karakorum and Hindukush. It also has the highest density of peaks above 7000m, the K2 and some of the biggest glaciers in the world.

As we follow the Karakorum Highway, the landscapes change around us. The rolling hills with lush deciduous forests grow into mountains of unfathomable height covered in conifers. After passing the Nanga Parbat, an iconic 8000m peak that is called mountain of death by locals, the vegetation becomes less and less. When we arrive in Gilgit-Baltistan, we are in a full-fledged desert cut-off from any rain by some of the highest peaks in the world. All we see around is stone that reaches from the ground up into the sky.

Living in harmony with nature

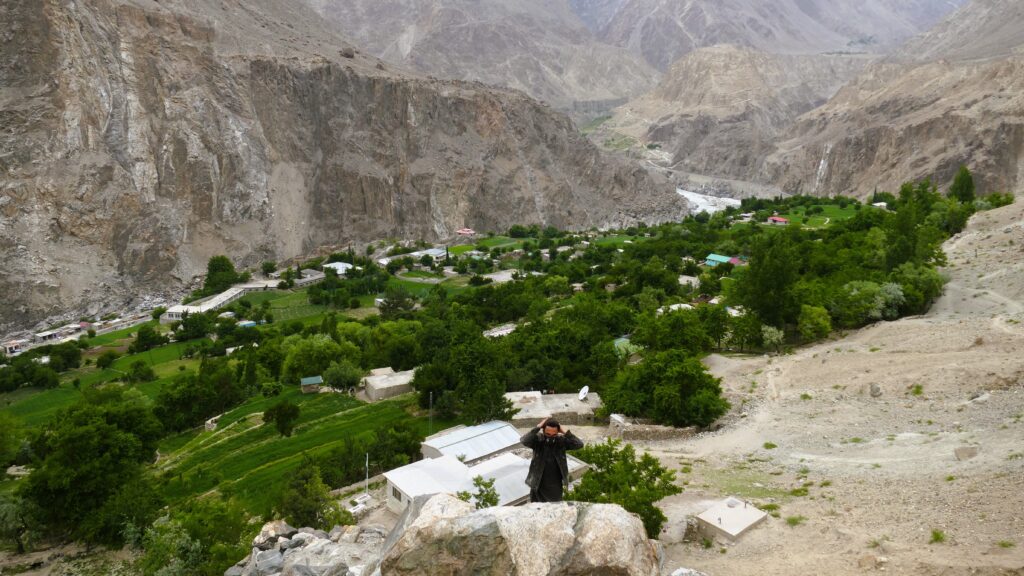

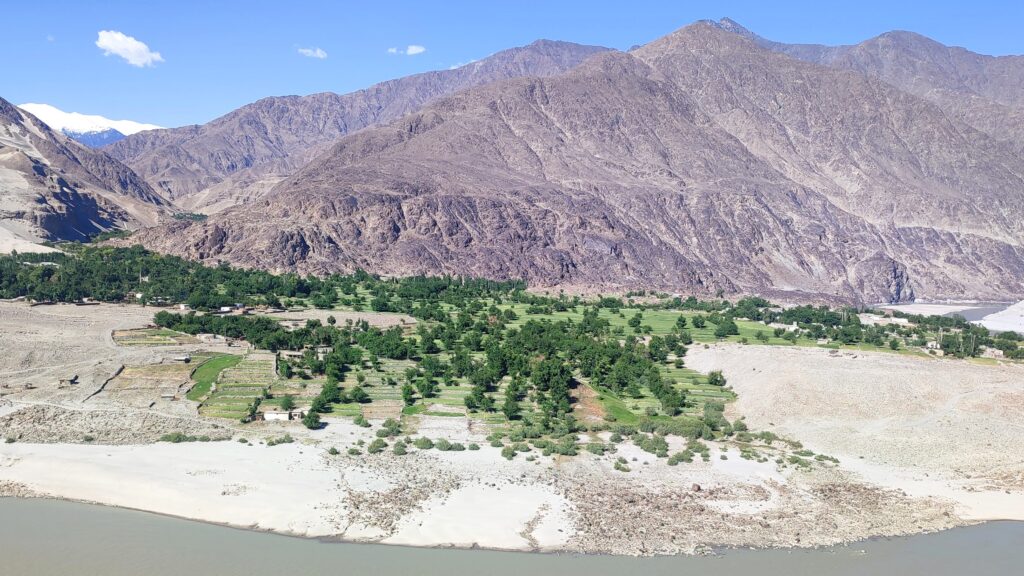

This landscape is not only an opposite to the spaces most people live in, but also a window into former times, when there was mostly wilderness without influence by humans. In the lowlands, we followed roads surrounded by farmland and settlement, with space for wilderness left only in small patches in between a landscape that is completely shaped by humans. In Gilgit-Baltistan, the natural conditions turn this dynamic around. Since there is barely any rainfall throughout the year, the only water sources are melting snow and glaciers. This means all villages including their agricultural fields are cramped by the rivers that are people’s sole lifeline.

While human settlements often look like grey prisons in a sea of green nature, here villages are green oases inside a sea of rock. Each house is surrounded by fields and trees that are the only greenery in the landscape. Witnessing this, we really feel that humans cannot only destroy habitats, but also create new ones.

This feeling is accompanied by a fascination for how connected locals are to their natural environment. Because they depend so closely on natural dynamics, they studied and utilized them for thousands of years and are deeply aware how crucial and fragile nature is.

A remote and forgotten region

How little this dependency has changed even in the last decades, is especially interesting to us after our experience with living in the Alps. They are home of modern alpinism, alpine sports and mass ski tourism and have probably been changed more within the last hundred years than any other mountain range in the world. On the contrary, villagers in Gilgit-Baltistan often still live like a hundred years ago without reliable electricity, running water our gas supply. The only energy sources are local hydropower and firewood, the latter must be sourced from trees grown by each villager themselves as there are no trees growing naturally.

That Gilgit-Baltistan is so ‘under-developed’ is not only result of its remoteness, but also its political situation. It is officially considered part of the disputed Jammu & Kashmir region and wedged in between Pakistan proper, India and China. Even though it is in reality controlled by Pakistan, it is not a fully-acknowledged province of Pakistan and the government has done little for its development for several political reasons. The region has been left to itself since India & Pakistan partitioned and no chance to develop by itself being cut-off from the rest of Pakistan.

NGOs step in

In the 1990s, several NGOs started working in Gilgit-Baltistan or were newly-founded to finally improve people’s life by supporting with and educating them about sustainable natural resource management. These are on one hand rural development organizations like the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme or the Gilgit-Baltistan Rural Support Programme , on the other hand nature conservation organizations like WWF or BWCDO.

In Skardu, capital of Baltistan, we meet Shazia, a social mobilizer and Aktif, a conservation officer, from WWF Pakistan to learn more about their work. We quickly learn that the dependency and deep connection of locals to natural dynamics also influences their work. The vast majority of Gilgit-Baltistan consists of rugged mountains that are completely unsuitable for any human use, not to mention largely inaccessible. This means that many threats like habitat loss and fragmentation or pollution are a much smaller issue here than in most other places. What remain issues are hunting and unsustainable resource use, so WWF and BWCDO, who we also met in Skardu, focus on tackling these specific topics together with local communities.

Protecting nature = protecting people

Beyond that, WWF runs several projects focused on sustainable development of rural villages, so humans and nature can thrive in harmony. They provide or support water filtration systems, school education, tree plantations and green houses with the aim of enabling communities to live independently and safely. At first glance, we are surprised that WWF focuses on these kinds of projects here as we do not see any direct connection to protecting wildlife. But after spending a whole day with Shazia, Aktif and many villagers, we understand their motivation. The people of Gilgit-Baltistan have a deep connection to their land and they are the stewards of this landscape. We learned how much they love their wildlife when we talked about snow leopards and trophy hunting with them. But we also learn that many live in the simplest conditions and that their livelihoods are fragile, just like the ecosystem around them. Supporting those livelihoods, making them independent from imports and empowering them actively helps their efforts of preserving the nature around them, which is so unique because it has remained largely unchanged.

Building local structures

We learn how tightly interwoven the lack of governance, the work of NGOs and local structures are when we talk about when this kind of work began. The Aga Khan Rural Support Program is the pioneer of NGO work in Gilgit-Baltistan and it laid a foundation that has become crucial for organizing the region today. They encouraged villages to set up village committees and so-called ‘local support organisations’ (LSOs) that bundle several villages. These have functioned like local parliaments as democratic representation and structures were barely present in the 1990s. They have been so successful that they are now widespread across Gilgit-Baltistan and these LSOs are the first contact for any outside organization that wants to do something in Gilgit-Baltistan.

In this way the Aga Khan Rural Support Program has also turned the problem that Gilgit-Baltistan lacked many governmental organs and national support into a strength by empowering these committees to make confident decisions about what should happen with their land and money. Shazia tells us that the LSOs are nowadays openly approaching them with lists of things that their villages need and in cooperation they come up new projects ensuring broad support among locals.

The climate crisis threatens everything

Another realization that hit us hard in Gilgit-Baltistan that it is not always in one’s own hands to protect local biodiversity. Despite the great work that NGOs and locals are doing, Gilgit-Baltistan’s ecosystem is in great danger and there is nothing the inhabitants can do about it. The climate crisis is threatening the foundation of life of local wildlife as well as people.

Everything here is closely tailored to the very specific and harsh natural conditions of the region. Only through this can animals and humans live in a desert that faces drought year-round, freezing cold temperatures and infertile soils. But these conditions are changing quickly. Raza from BWCDO tells us that Baltistan has experienced water shortages in spring in many of the last years as snowfall has decreased and hence snowmelt, the only water source in spring. This causes a lack of drinking water, delay of crop-sowing and power shortages as hydropower is the only available energy source. On the other hand, floods during summer have increased. Houses in Gilgit-Baltistan are designed specifically for local conditions meaning they are very vulnerable to heavy rainfalls and floods, which have rarely occurred in former times. Similarly for animals, this creates water and food shortages, especially in winter and spring.

Aware and afraid, but not alone

For these reasons, learning about life in Gilgit-Baltistan has been very eye-opening for us. Never before have we seen a region so directly hit by the effects of climate change. Effects that we have experienced with our own eyes when we had about two hours of electricity per day or when we saw glaciers that have drastically shrunk in just a few decades. And also, never before have we witnessed how aware local people are to the threats the natural environment faces. “We need all the help we can get to save our glaciers,” a local told us on our visit to his farm. Locals feel the changes but are ready to adapt. And in a disputed region where they are practically left alone by their own government, NGOs have stepped up and provided the help that is needed. Not solely focusing on protecting nature, and not even only on local livelihood development. The case of Gilgit-Baltistan shows that one cannot be without the other. People depend on nature, and nature, at least in the places where people have settled down, needs good guardians.